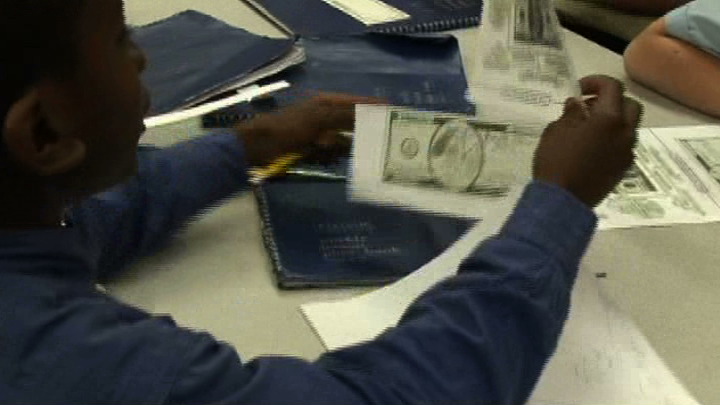

Production still of the Extended Play episode, Mel Chin: “Fundred” at George Jackson Academy. © Art21, Inc. 2008.

I first encountered the work of Mel Chin in 2011 while on a tour of the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, chaperoning a group of eleventh-grade students from Kensington Culinary High School. Lining the walls of the public studio space were hundreds of Chin’s “Fundreds,” designed by students from the Philadelphia region. It may have been the first time I’d experienced a contemporary artist using social engagement practices to involve youth directly. Mel Chin created the Fundred Dollar Bill Project in response to the catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina and the need to rebuild New Orleans. He designed a template for a blank 100-dollar bill, created a lesson plan and a website, and shared it with the public, specifically inviting schoolteachers and their students to participate. Chin proposed some big questions: What would America’s children want for their future? What if policy makers could see the real faces of children who are affected by the money sparingly doled out, whose health and safety was in the balance?

“Giving children a chance to share their experiences and dreams makes me feel seen as a teacher, too.”

The Fundred Dollar Bill Project continues, thirteen years after its inception, as part of Operation Paydirt, which aims to bring awareness to the issue of lead exposure and children’s health and development. Both Kensington High School and Christopher Columbus Charter School—where I currently teach middle-school art and technology—are in areas of Philadelphia with high risk levels of lead exposure (the schools measure 7 and 8, respectively, out of 10 on a scale created by the US Census lead risk map. These numbers make me wonder if my students’ exposure to lead may explain some of the challenges they have in the classroom. Knowing that a contemporary artist like Mel Chin is building awareness about environmental justice and giving children a chance to share their experiences and dreams makes me feel seen as a teacher, too, by calling attention to toxic classrooms and hopefully triggering larger conversations about funding for education.

Mel Chin. Too Me, 2017. Taken at City Hall, Philadelphia, PA as a part of Monument Lab with Mural Arts. Granite, steel, bronze, glass, commercial-grade aluminum ramp system, marine plywood, pigment, non-slip coatings, and people. Photo: Steve Weinik.

“By using themes to inspire their work, my students found more individualistic ways to express themselves.”

My second encounter with Chin’s work was in the summer of 2017, immediately after my first Art21 Educators Summer Institute. For a project called “Monument Lab,” the Philadelphia Mural Arts program invited a roster of national artists to make temporary monument installations around the city. In a moment of synchronicity, the installations appeared to be a response to the 2017 white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the calls for dismantling of monuments of oppression throughout the country. One day I walked into the courtyard of Philadelphia’s City Hall to find two large stone pedestals topped with half-wall glass enclosures, near the center of the space. Both pedestals had long ramps behind them, filling up half the courtyard but allowing anyone to access the each pedestal via a gradual slope. My initial reaction was “Ugh! Bad design! Why are these ugly metal ramps there? They’re taking up all the space!” But then I realized what I was seeing: Mel Chin’s work, Two Me (2017), placed in the center of our city, may have made things slightly uncomfortable but created an opportunity for anyone, regardless of ability, to become a monumental figure. The work presented the ideas that all voices are worthy of being heard, all bodies are worthy of being seen, and all people deserve equal representation under the law. Seeing this work made me wonder: Am I allowing my students’ voices to be heard? Am I treating my students equitably? What would happen if I stepped off the teacher’s podium and allowed more opportunities for my students to be front and center?

I held these ideas in my heart as I embarked on my year as an Art21 Educator, in the seventh cohort, and implemented contemporary-art teaching strategies in my classroom. My students and I delved into themes like “Safety and Protection,” “Beauty and Identity,” and “Informed Opinions.” By using themes to inspire their work, my students found more individualistic ways to express themselves. Instead of presenting myself as the main source of artistic knowledge in the room, I taught my students to conduct research and become experts about artworks that they could teach to their peers. Rather than grading final products during my prep time, I spent more one-on-one time with students in class, as they self-evaluated their artistic process and production. Each of these changes in my practice let me step back while allowing my students to step forward.

Isaiah Zagar. Image of mosaic by artist Isaiah Zagar, over 200 of these public works decorate Philadelphia, PA. Image provided by the author.

At one point in the year, I explored the theme of monuments with my fifth graders. We researched public art in Philadelphia, and we investigated what kinds of monuments and public art could be found. Students mapped the examples closest to our school and planned a walking trip to visit them. They found murals, by Isaiah Zagar, claiming Philadelphia as the “Center of the Art World” and other murals celebrating the 76ers basketball team and depicting the immigration stories of the local Vietnamese community, in addition to sculptural beacons marking the gateway between South Philly and Center City. My students considered the messages and purposes of the public art they’d found, and they described other examples from their neighborhoods, which they mapped to show where they felt safe or not. We discussed how public art can transform a neighborhood—providing visual safety nets—and the students designed their personal monuments and murals, ones they wished to see where they lived. I hope that this process of investigation, analysis, and design around art in public space will empower my students to consider how they can contribute to their communities.

Mel Chin models how one can create a platform for new voices. His monument project reinforced a shift in my teaching, from technique-focused lessons to more content- and inquiry-focused ones. While I still spend time on topics like color mixing, pencil shading, and clay construction techniques, I also discuss artwork and brainstorm ideas with my students and listen to their points of view. An artist teacher can create a platform for students, especially youths, to speak, which ultimately makes something bigger and more powerful than what one could accomplish on one’s own.